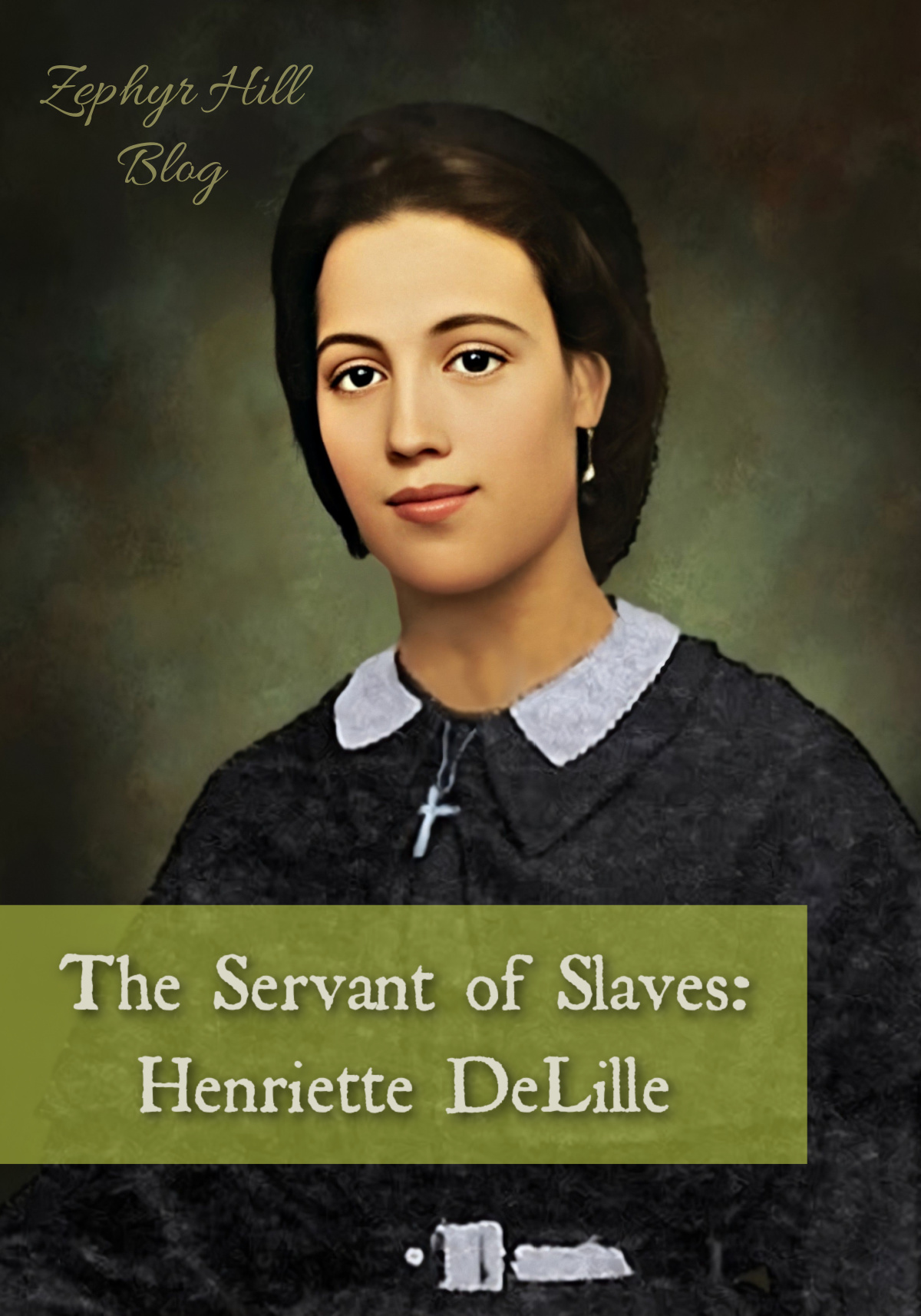

Born in 1812 on Burgundy Street in New Orleans and baptized a Catholic, Henriette had a French father and a Creole mother, with French and Spanish and African ancestry. Never legally married, Henriette’s parents operated under a system called placage, common in the French colonies where white men faced a shortage of wives of the “ideal” color and class. These “kept women” of African, Indian and Creole descent were called placees. Although not legal, these relationships were recognized among the free minority populations; the women and their resulting children (who would adopt the father’s surname) lived comfortably and moved freely within an active social circle.

Thus, young Henriette led a comfortable life in the city, schooled in French literature, music and dancing, with her future life destined to look like her mother’s. But Henriette was absorbing other things in her upbringing, namely the teachings of the Catholic faith. Inspired by her love of God and His laws, she would later become an outspoken opponent of the placage system; true, it was an easier life for bi-racial women, but it represented a violation of the holy sacrament of marriage, instituted by Christ Himself, and an affront to the dignity of women.

In 1827, at the age of fourteen, this gracious and well-educated young lady began to educate other Creole girls at Saint Claude School. Over the years, as she brushed elbows more and more with the underprivileged, the seeds of her future mission were being planted. It was around this time, too, that funeral records indicate teenaged Henriette might have given birth to two little boys, both named Henry Bocno in succession and both who died very young. This points to the possibility that she had already been “placed” with a wealthy man, but no conclusion has yet been reached by historians about these records.

But sometime after receiving the powerful sacrament of confirmation at age 22, Henriette’s life began to turn in a different direction, and big changes were imminent. A year later, her mother tragically suffered a nervous breakdown, and when the court declared her incompetent, that left young Henriette in control of the family assets. These she used to find a suitable place for her mother; the rest was sold. Henriette, whose only recorded written words were “I believe in God. I hope in God. I love God. I wish to live and die for God,” had always labeled herself a “free colored person” even though she and her family were octoroons (or 7/8 white). Because of this she was denied entrance into the exclusively white Ursuline convent.

Finding another way through the racial red tape of the day, Henriette took the proceeds of her asset sale and organized a modest (but officially unrecognized) gathering of nuns called the Sisters of the Presentation. This original group included Henriette, seven Creoles and a young French woman.

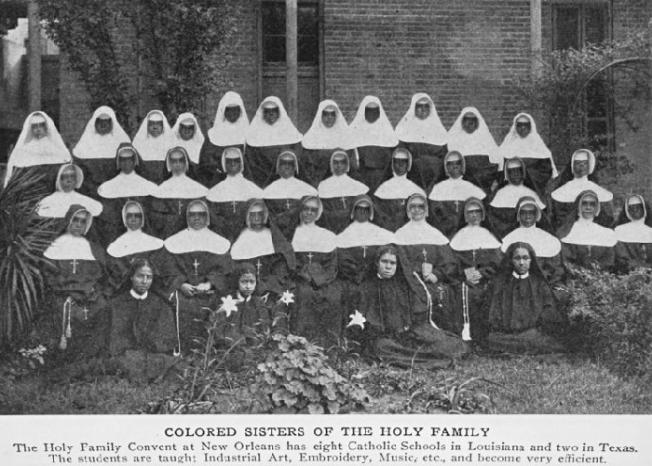

The Sisters of the Holy Family, the name of her order which was eventually sanctioned by the Church, took shape during the 1840’s. The founding members took their vows on bended knee in old Saint Augustine Church in New Orleans (below). From Henriette and her fellow sisters, slaves received free education and catechism, even though teaching slaves put the nuns at risk of imprisonment or even death. They counseled free Creole women to marry men of their own class, and encouraged slave couples to have their unions blessed by the Church. The elderly, sick and poor also found refuge in the home that DeLille made possible.

In 1853, Henriette and her sisters nursed the sick and dying during New Orleans’ horrific yellow fever epidemic.

Twenty years after taking her vows and spending herself in the service of others, Henriette DeLille passed away at the young age of 49 from illness, while New Orleans was under occupation by the Union army. This obituary appeared in a local New Orleans paper:

Last Monday died one of these women whose obscure and retired life was nothing remarkable in the eyes of the world

but is full of merit before God… Without ever having heard speak of philanthropy, this poor maid had done more good

than the great philanthropists with their systems so brilliant yet so vain.

Courage is most certainly one of Henriette DeLille’s outstanding virtues. She boldly left her comfortable life behind, and even placed herself at odds with family by refusing to hide her African ancestry. Advocating against an entrenched social system and defying the law to give slaves an education, Henriette was a fighter who put her life on the line for love of neighbor. Showing great faith and hope, she founded a religious order for biracial women, knowing full well that approval was not assured, but trusting that God would work out the details and help it to flower.

Her cause for canonization was opened in 1989 and advanced by Pope Benedict XVI in 2010. She is the first native born American of African descent whose cause has been opened by the Church.

The stylized painting below not only capture’s Henriette’s compassionate and generous nature, but is imbued with that marvelous character that only New Orleans possesses. The lanky green shutters, old brick walls and palm fronds all vie for attention among a gathering of people, varied in both country and color. In 2011, the City of New Orleans named a street after Henriette.

Detail from a work by artist Ulrick Jean-Pierre,

which is hanging at the Sisters of the Holy Family Motherhouse in New Orleans

When death freed her from the bonds of Earth, Henriette left behind 12 fellow sisters; by 1909 the order had grown to 150. The sisters are still active today, with more than 200 members who serve the poor by operating free schools for children, as well as nursing homes.

Sisters of the Holy Family, 1899 Buyenlarge/Getty Images

The photo below shows the sisters again in 1905.

In 2013, a miracle attributed to her intercession was approved!

Venerable Henriette DeLille is a reminder for all of us to never forget the vulnerable, the unseen, and the voiceless. God looks not at color or class, but the heart.

Credit: The title image in this post is a colorized photo painting by Saints Alive Art Studio.

Leave a Reply